History of Kilimanjaro

Humans have lived on or around Mount Kilimanjaro since at least 1,000 BC. Stone bowls have been found and dated back to that time. It is logical to assume that Kilimanjaro would have been a desirable place to establish a home. Kilimanjaro is a sustainable source of flora, fresh drinking water and materials for building such as mud, wood, stones, vines etc. Unfortunately not much else other than the stone bowls and the resources in the form of hard evidence or passed down oral accounts has survived. The pre-colonial history of the region has been lost with time.

Over the last 500 years:

- the mountain has at various times acted as a navigational aid for traders travelling between the interior and the coast

- a magnet for Victorian explorers

- a political pawn to be traded between European superpowers who carved up East Africa

- a battlefield for these same superpowers

- a potent symbol of independence for those who wished to rid themselves of these colonial interlopers.

Unfortunately, little is known about the history of the mountain during the intervening two thousand five hundred years. So while we can assume many things about the lives of Kilimanjaro’s first inhabitants, we can be certain about nothing and if Kilimanjaro did have a part to play in the pre-colonial history of the region, that history, and the mountain’s significance within it, has, alas, now been lost to us.

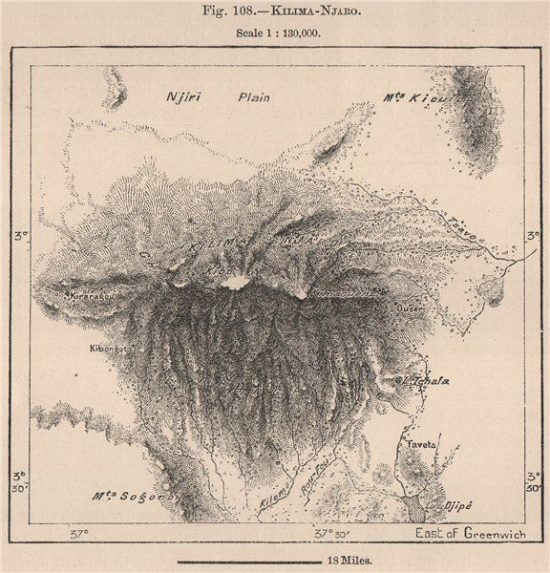

It is generally accepted that the outside world became aware of Kilimanjaro during the first or second century AD. A hearsay account repeated by Ptolemy of Alexandria, astronomer and the founder of scientific cartography, wrote of lands in East Africa lying near a wide shallow bay and where, inland, one could find a ‘great snow mountain’. While there was a lot of commerce conducted in the form of trade between the natives of East Africa and the world there are very few historical mentions of Kilimanjaro for the next 1200 years.

After 1500 AD the Portuguese displaced the Arabs as the major traders of the land. They explored the inland more than previous visitors to the region. The Portuguese made mention of Kilimanjaro in a book, Suma de Geographia, published in 1519, with an account of a journey to Mombasa by the Spanish cartographer, astronomer and ship’s pilot Fernandes de Encisco believed Kilimanjaro to be the source of the Nile river.

The 1800s brought European and British interest in the Mountain. It was accepted belief that the great white mountain a couple of hundred miles from the coast was the source of the Nile. Interest in the ‘dark continent’ was further aroused by the arrival in London in 1834 of one Khamis bin Uthman. The envoy of the then-ruler of East Africa met with Britain’s leading African scholar, William Desborough Cooley. A decade after this meeting, Cooley wrote his lengthy essay The Geography of N’yassi, or the Great Lake of Southern Africa Investigated, in which he not only provides us with another reference to Kilimanjaro – only the fifth in 1700 years – but also becomes the first author to put a name to the mountain:

The most famous mountain of Eastern Africa is Kirimanjara, which we suppose, from a number of circumstances to be the highest ridge crossed on the road to Monomoezi. Two pioneering explorers, Richard Francis Burton and John Hanning Speke set off to find for themselves the source of the Nile, crossing the entire country we now know as Tanzania in 1857. This was also the age of Livingstone and Stanley, the former venturing deep into the heart of Africa in search of both knowledge and potential converts to Christianity.

Yet for all their brave endeavors, it was not Richard Francis Burton and John Hanning Speke to be the first European to set eyes on Kilimanjaro. Rather it would be a young Swiss-German Christian missionary by the name of Johannes Rebmann.

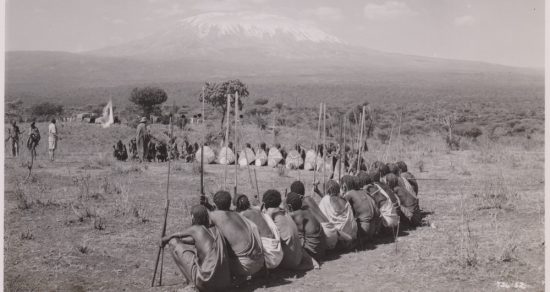

Rebmann worked with another man Dr. Krapf helping convert the native population to Christianity. Eventually they hear of a land called Chagga with a great mountain called ‘Kilimansharo’. From other sources, Krapf and Rebmann also learned that the mountain was protected by evil spirits (known in the Islamic faith as djinns) who had been responsible for many deaths, and that it was crowned with a strange white substance that resembled silver, but which the locals simply called ‘cold’.

The name Kilimanjaro has no certain origin, but one of the most popular theories is that it came from KILMA NJARO meaning “shining mountain” in Swahili. The shiny snow on the peak led nearby residents to believe that evil spirits guarded the mountain. This myth could also explain why some referred to NJARO as a demon that caused cold.

Because they saw fellow tribe members attempt the climb only to disappear or to return deformed from frostbite, the Chagga people—who live at the base of the mountain—for centuries had no desire to climb the mountain they believed was full of evil spirits.

A slave dealer was eventually persuaded to take Rebmann to Chagga in 1848, Krapf was at the time to ill to travel. Rebmann travelled along a route where caravans typically travelled under armed escort – Rebmann, accompanied by the slave dealer and eight porters, set out for Chagga on 27 April 1848. A fortnight later, on the morning of 11 May, he came across the most marvelous sight:

“At about ten o’clock, (I had no watch with me) I observed something remarkably white on the top of a high mountain, and first supposed that it was a very white cloud, in which supposition my guide also confirmed me, but having gone a few paces more I could no more rest satisfied with that explanation; and while I was asking my guide a second time whether that white thing was indeed a cloud and scarcely listening to his answer that yonder was a cloud but what that white was he did not know, but supposed it was coldness – the most delightful recognition took place in my mind, of an old well-known European guest called snow. All the strange stories we had so often heard about the gold and silver mountain Kilimanjaro in Jagga, supposed to be inaccessible on account of evil spirits, which had killed a great many of those who had attempted to ascend it, were now at once rendered intelligible to me, as of course the extreme cold, to which poor Natives are perfect strangers, would soon chill and kill the half-naked visitors. I endeavored to explain to my people the nature of that ‘white thing’ for which no name exists even in the language of Jagga itself…” ~ Johannes Rebmann from his account of his journey, published in Volume I of the Church Missionary Intelligencer, May 1849

An extract from the next edition of the same journal continues the theme:

The cold temperature of the higher regions constituted a limit beyond which they dared not venture. This natural disinclination, existing most strongly in the case of the great mountain, on account of its intense cold, and the popular traditions respecting the fate of the only expedition which had ever attempted to ascend its heights, had of course prevented them from exploring it, and left them in utter ignorance of such a thing as ‘snow’, although not in ignorance of that which they so greatly dreaded, ‘coldness’.

Rebmann made a second trip to Kilimanjaro in November of the same year and was provided with good weather conditions, resulting in his clearest view of Kilimanjaro. He wrote a most accurate and comprehensive description of the mountain that had yet been written:

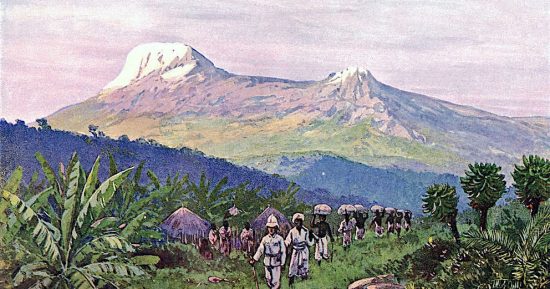

There are two main peaks which arise from a common base measuring some twenty-five miles long by as many broad. They are separated by a saddle-shaped depression, running east and west for a distance of about eight or ten miles. The eastern peak is the lower of the two, and is conical in shape. The western and higher presents the appearance of a magnificent dome, and is covered with snow throughout the year, unlike its eastern neighbor, which loses its snowy mantle during the hot season.

On this second trip Rebmann was also able to correct an error made in his first account of Kilimanjaro: that the local ‘Jagga’ tribe were indeed familiar with snow and did have a name for it – that name being ‘Kibo’!

A third and much more organized expedition in April 1849 – at the same time as the account of his first visits of Kilimanjaro was rolling off the presses in Europe – enabled Rebmann, accompanied by a caravan of 30 porters to ascend to such a height that he was later to boast that he had come ‘so close to the snow-line that, supposing no impassable abyss to intervene, I could have reached it in three or four hours.’

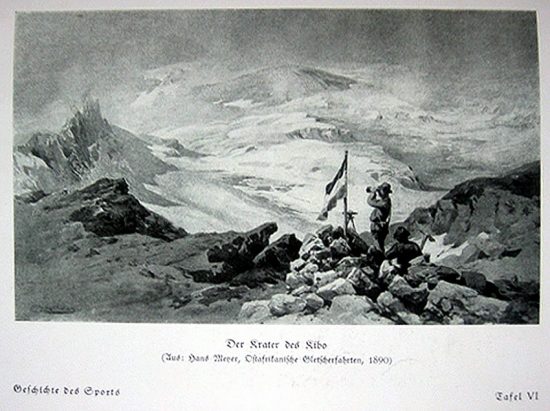

In 1889, German geographer Hans Meyer and Austrian mountain climber Ludwig Purtscheller were the first to climb Kilimanjaro, shortly after Tanzania had been annexed by Germany. Since Kilimanjaro was now the highest point in the German Empire, Meyer promptly named the topmost peak on the crater rim Kaiser Wilhelm Spitz, in honor of the German emperor. After Tanzania gained its independance in 1963, the peak was renamed Point Uhuru (Swahili for “freedom”).

Kilimanjaro has gained prominence lately as one of the seven summits, the highest mountains on each of the seven continents. But rising in isolation 17,000 feet above the surrounding plain, and the breathtaking climatic transitions, it is an awesome — and rewarding — mountain in its own right.