Climbing Kilimanjaro

Climbing Kilimanjaro is an unforgettable experience and an opportunity to climb the world’s tallest free-standing mountain. Once you have chosen which route to climb, you will want to know more information about Kilimanjaro and what to expect from the trek.

The important factors to consider such as; what is the best month for climbing Kilimanjaro, what are the temperatures on the mountain, what are the trail conditions like, how far will I walk and how do I cope with altitude sickness? The answers to these questions and many more can be found here the following pages of my website and in this section I will cover the following topics:

Weather

There are two wet seasons a year on Kilimanjaro that you will want to avoid. The trail conditions in the rain-forest can deteriorate quickly with heavy rainfall making the paths difficult to negotiate; you may have to start your trek further down the mountain if the tracks for the vehicles become impossible to drive on.

Temperatures in the various climate zones on the mountain remain fairly constant all year round; however the range in temperatures between the rainforest and the arctic summit zone is vast and can differ by up to 50 degrees. You will trek through five ecological zones during your Kilimanjaro climb and you should be prepared for any weather condition imaginable. With good planning, proper clothes and equipment, this should not be of concern. No matter which route you decide to climb Mount Kilimanjaro, your daily routine will basically be the same.

Guides & Porters

It is a requirement to have a licensed guide and staff with you on Kilimanjaro. The crew consists of a team of individuals with different tasks. Most Kilimanjaro guides are professionals who have climbed and summited countless times. They are very experienced, having dealt with a breadth of issues while on the tour.

Guilds are required to be licensed by Kilimanjaro National Park, where they must complete extensive training. They are required to learn about the history of the mountain, the geography, the effects of altitude, and how to handle all emergencies. Most guides are fluent in English and are very personable.

Kilimanjaro Porters Assistance Project (KPAP) aims to improve the working conditions of porters on Mount Kilimanjaro and other hiking areas in Tanzania and was founded in 2004.

A set of guidelines drawn up by KPAP include:

- Porters must me appropriately dressed for the trek with warm and waterproof clothing.

- Porters must be adequately fed on the trip.

- The load carried per porter must be limited to 20 kgs.

- There must be adequate porter to client ratios; 2 porters per client on the Marangu Route, 3 porters per client on the on Rongai, Machame, Shira, Umbwe routes, 3 – 4 on the Lemosho Route.

- Porters, guides and cooks must be provided with a set wage.

- Clients should be advised to tip staff appropriately for their services at the end of the trek.

Resources provided by Kilimanjaro Porters Assistance Project (KPAP) include:

- Language classes

- Classes in environmentally sustainable tourism

- Healthcare and first-aid classes

- Training in providing customer services

- Classes to know their rights

- Legal advice

- Assistance in micro-finances to improve their family’s living conditions

- Guarantee of an education for their children

- Year-round employment possibilities

- Access to an affordable equipment and clothing store

Once on the Mountain, your guide is your mentor and it is his duty to advise, lead, support and encourage you to safely achieve your personal goal, then to bring you down to the gate again. He will hike with you and answer any questions you have about the mountain. It is important that you work closely with your guide and follow his advice.

If you feel unwell at any time you must be honest and tell your guide.

The guide recruits the mountain crew (porters, assistants, chefs) and it is his responsibility to see that the crew work efficiently and everything runs smoothly and safely. Your guide is responsible for managing many duties, as well as your safety. One of the most important factors when climbing Kilimanjaro is your Guides and Porters. It will be their knowledge, assistance and support that will get you safely to the summit and down again!

The porter to client ratio is generally a calculation of 2.5 porters to 1 client. The maximum load a porter should carry is 15 kg. Porters carry client’s back-packs, food, trekking equipment and general supplies as well as their own personal gear. Their load is weighed at the entry gate. More porters may need to be allocated to the climb crew if loads exceed National Park regulations.

Porters have a tough job. They carry the climbing equipment between campsites and set up everything so it is ready when your team arrives. Not only do they carry the shared equipment, like tents, chairs, tables, lanterns, stove, gas and water, but they also carry the personal items of the clients. Their load is limited to 20 kgs by the park service.

Your team will also include a highly skilled mountain chef who is responsible for knowing any dietary restrictions of each climber and adjusting meals accordingly. Nearly all meals on the mountain are prepared fresh- except for the occasional bagged lunch. Preparing and cooking food at altitude (often in bad weather conditions) takes skill and patience, these guys are superstars!

Altogether, this team of individuals will make your climb as comfortable as possible. Though they make a decent living by Tanzanian standards, they are on the mountain many days out of the year and have a physically demanding job. They depend on tips, and climbers should budget a substantial tip for their climbing crew.

A general estimate, for your budget, per Kilimanjaro climber is roughly $175 to $250 per person depending upon the following factors: the number of people in your group, the number of the porters (which is often quite large), number of guides, cooks, and sometimes the route. It is impossible to predict an exact tip in advance because it really depends upon how much gear and weight is carried up the mountain. There is not a de facto standard of tipping for all companies, it’s only a recommendation from organizations, NGOs and the Tanzanian government.

Food & Water

Food

The menu on Kilimanjaro is designed to ensure your food intake matches your level of exertion. It will provide you with a good balance of protein, carbohydrates, fruit and vegetables. When you are at altitude you could start to feel nauseous and your appetite may be suppressed, so the meals prepared at high altitude usually contain more carbohydrates and less protein to help you digest faster.

The food on Kilimanjaro is carried and prepared by your porters and cook. You will be served a hot breakfast, either packed lunch, or lunch at camp and an evening meal. In addition to your three meals a day you will also have afternoon tea, with popcorn or biscuits and fresh fruit. You will have a flask of hot water at meal times to make tea, coffee or hot chocolate with. Water is collected by the porters from the streams near the camps, which is boiled and cooled for drinking. You should ensure that you are drinking at least three liters of water a day, more when at high altitude. Sample meals include:

Breakfast – ‘Bed tea’ (with a smile), chapatti, oat porridge, sausages, scrambled eggs, French toast with honey, toasted bacon and cheese sandwich, fresh fruits or fruit filled pancakes.

Lunch boxes may contain – samosa, sandwich, fresh fruit, boiled egg, chopped salad vegetables (carrot, tomato, pepper), cashew nuts, chocolate bar, cake and fruit juice. A hot drink will be prepared at the stopping place. Energy snacks may be provided for the summit e.g. chocolate, nuts, popcorn or biscuits.

Dinner starts with a type of soup, (e.g. leek and potatoes, pumpkin, carrot and lentil with coriander), spicy chicken soup, or fresh salad vegetables with mayonnaise and is followed up with – fried tilapia fish fillet with fries and salad vegetables, beef goulash, spicy fried chicken with vegetable sauce and rice, pasta with mixed vegetables in a rich tomato sauce, Tanzanian banana stew (Ndizi), beef and rice (Nyama na wali)

Desert may be – Fresh fruits, fried bananas with chocolate sauce, Tanzanian pancake with honey and yogurt.

Hot drinks with each meal include (tea, coffee, milo, chocolate).

You may wish to bring your own snacks to provide well deserved treat, or energy boost! Chocolate is generally the best answer and if it has nuts, even better. Whatever you choose though make sure it is a favorite treat and not a ‘power bar’, or ‘energy gel’. If you are suffering from altitude sickness your appetite may be suppressed and these snacks may become a good supplement to your meals, so make sure it is something that you enjoy eating! A powdered energy drink such as Gatorade sport is also a good source of energy and will help with the taste of the water if you have been using iodine tablets.

Water

You will need to consume more water on Kilimanjaro than you would normally drink on an average day at home to keep properly hydrated. This is due to the physically exertion of walking between 4 – 8 hours per day and the effect of being at high altitude.

Remember to drink at least 4 liters of water ever day when above 12,000 feet.

Water is provided by the porters who will fetch water from the streams near the camps on Kilimanjaro. The water is then boiled by the porters, which should be fine for drinking. However you may wish to bring additional water treatment methods such as; water filters or Iodine tablets if you have a particularly sensitive stomach.

High on Kilimanjaro the water is extremely clean, except for those few places where it has been contaminated by human waste. The lower you are, elevation-wise, and the closer you are to campsites and popular trekking routes, the more likely it is not clean. Wherever you are, it’s a good idea to boil or treat your water at all times.

Water is readily available at most camps and huts. At worst, such as Barafu Huts on Kilimanjaro, it’s a half hour’s easy hiking away.

Accommodations on The Mountain

Campsite or Huts

Hut Reservations

Hut reservations are only required for the Marangu Route. The huts on the other routes (Mweka, Umbwe, Machame, Shira Plateau) are merely burned-out metal shells often filled with trash. Most non-Tanzanians who use these other routes bring a tent, and the huts are used only by the guides and porters, who do not seem to mind their state of disrepair. If you do decide to use the huts on these other routes, it is a matter of first come, first serve.

Marangu route is the only route with dormitory style mountain huts to sleep in at night. There are 60 bunk beds each at Mandara and Kibo Huts, and 120 bunk beds at Horombo Hut. There are communal dining areas and basic toilet and washing facilities. Rongai route climbers who join Marangu route for the summit attempt and for descent do not have access to the huts for sleeping, this is KINAPA policy.

If you do not have a tent and really must stay in huts as you ascend the mountain, the ones on the Marangu Route are in good condition. There are three main huts (Mandara Hut, Horombo Hut, and Kibo Hut), spaced a day’s walk apart. However, each of these huts are surrounded by a virtual village of buildings, and the names refer to the old huts that existed long before the other structures were built. Some of the additional buildings are for porters and guides to sleep in; others are for park officials and small shops. Tourists generally sleep in the original huts.

Reservations must be made at the park offices at the Marangu Gate. Your outfitter will arrange these reservations for you as part of your climb.

When you arrive at each hut complex on the Marangu Route, you or your guide must go straight to the caretaker’s office and show your reservations to park officials, who will help you find your hut and sleeping quarters. As with most other things, your guide will take care of this for you.

There are no facilities in the huts except for bunks; you need to bring a sleeping bag and sleeping pad. Cooking must be done outside. At both Horombo and Mandara Huts, there are separate facilities for washing—small bathroom buildings, with cold showers and toilets. The toilets at Kibo Hut are like toilets on other routes on the mountain—big earthen pits. There is no natural water supply at Kibo Hut, so there are no showers.

All other routes are camping only with long drop toilets and water that is carried and delivered by porters. The campsite areas make the most of the available terrain, with some having precarious ‘drops’ for the unsuspecting hiker. It is advisable that you familiarize yourself with the location of toilets before dusk.

Water is provided for personal washing but remember to use sparingly and keep in mind that there is no place ANYWHERE on any route to dump garbage. All trash is carried back down the mountain to the gate by the porters – this is a large volume of garbage for each group so be mindful of what you are “throwing” away. Each climber should carry a small plastic bag to collect personal garbage and give it to the porters at the end of each day.

Huts on Mount Kilimanjaro

- Mandara Hut Capacity / Beds: 84 Beds

Owner: TANAPA - Horombo Hut

Capacity / Beds: 84 Beds

Owner: TANAPA - Kibo Hut

Capacity / Beds: 58 Beds

Owner: TANAPA

Campsites on the Mount Kilimanjaro:

- Big Forest

- Simba

- Shira

- Machame Moir

- Buffalo

- Lava Tower

- Arrow Glacier

- Barranco

- Umbwe

- Millenium

- Mweka

- Horombo

- Mandara

- Kibo

- Barafu

- School

- Rongai Cave

- Rongai Second Cave

- Rongai Third Cave

- Kikelewa Caves

- Mawenzi Tarn

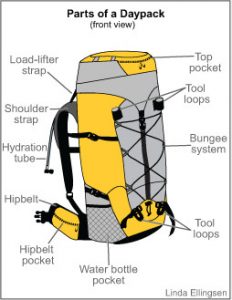

Day Pack

Normally you will not see your backpack from the moment you hand it to the porter in the morning to at least lunchtime, and maybe not until the end of the day. It’s therefore necessary to pack everything that you may need during the day in your daypack that you carry with you. Some suggestions, in no particular order: Be sure your day pack has a waist strap and good back and shoulder support.

- Water purifiers / filter

- 2 – 4 liters of water

- Lunch (supplied by your crew)

- Snacks

- Sweets

- Watch

- Rain gear

- Compass

- Whistle

- Sunglasses

- Sunhat

- First aid kit with essentials such as topical antibiotic, bandages, moleskin and prescription medicines

- Camera

- Film / batteries / digital card

- Chapstick

- Sunscreen

- Insect repellent (at lower altitudes)

- Toilet paper and trowel

- Guidebook

- Maps

- Money

- Passport

- Walking sticks and knee supports

- Extra fleece jacket

- Some extra layers of clothing in case the temperature drops

To pack your day pack efficiently, you should use plastic bags to separate items based on categories. For example, small bottles such as prescriptions, sunscreen, lip balm and hand sanitizer should be secured in a zip-lock type bag. Extra layers of clothing should also be put into larger bags. Paperwork, such as your passport and insurance documents into another bag. Heavier items should be placed close to the midpoint of your back to keep your center of gravity in-line with your spine. Placing heavy items near the top, bottom, left, right or rear of your day pack will cause you to lean forward, back, or to the side. If your day pack has compression straps, tighten them so that your items do not move around as you walk. Lastly, be consistent as to where you store your items (main compartment, side pockets, pant pockets, etc.), so that you do not fumble for your items when needed. A medium sized backpack, with the capacity of about 1,800 cubic inches (30 liters), is appropriate.

Mountain & Trail Conditions

The paths on the mountain are clearly marked and well maintained by the Kilimanjaro National Park staff, however but the trail conditions change dramatically depending on the ecological climate zone. Walking conditions are challenging and changeable, but relatively easy compared to the other mountains of the seven summits.

The lush rainforest area at the base of Kilimanjaro can be wet and slippery underfoot if there has been heavy rain. The alpine desert zone has a mixture of good clear paths and more challenging sections where you will have to scramble over large rocks such as the Barranco Wall. The ascent to the summit, Uhuru Peak, is covered in loose scree which can be slippery under foot; the use of walking poles can help with balance and save energy on the descent and finally the ice caped summit.

The terrain changes as you climb higher but are generally comfortable to negotiate with a good pair of 3-4 season waterproof walking boots; no specialist equipment is required to negotiate the trails on Kilimanjaro.

Daily Routine

Regardless of the route you choose, the daily routine when climbing Kilimanjaro generally remains the same. Hiking times range from 4 and 8 hours depending on the schedule and distance covered and regular breaks are taken throughout the day to ensure you are drinking enough water.

Porters arrive at the next camp in good time and will have collected water, set up your tents and have afternoon tea ready by the time you get there. Once you arrive at camp you will be provided with hot water to wash with and a chance to relax before dinner is served. It’s a good idea to wash up then put on the clothes you will sleep in underneath your evening clothes so that you are ready for bed.

Dinner is typically served around 18:30 and after your guide will come to your mess tent and talk to you about the next day’s hike and advise you on what to wear and carry in your rucksack. The evening is for you to relax, maybe a game of cards with a cup of tea, reading, or getting to know your fellow travelers. You will typically be in bed by 21:00 to rest for the next day’s hike.

Summit day, however is a different animal. You will generally set off around midnight and walk through the night aiming to reach Uhuru Peak close to sunrise. Once you have stopped briefly for the obligatory photo, you will then start your decent. Summit day will typically last between 10 – 16 hours depending on which route you choose and your pace. This is a physically and mentally demanding night and day, walking in absolute darkness with only your headlamp to guide the way and temperatures that can reach minus 25 degrees with wind chill is no easy feat, but if it was that easy then everyone would do it!

The mantra that you will hear from the guides and porters on Kilimanjaro in Swahili is ‘Pole, pole…..’, meaning – ‘slowly, slowly…’ no need to rush!

Safety & Altitude Sickness

Kilimanjaro is potentially hazardous, trekking at high altitude is dangerous. Various medical conditions may complicate matters on Kilimanjaro, especially any issues related to the heart or lungs. Additionally, certain medications may place climbers at a greater risk on the mountain. Therefore those intending to climb Kilimanjaro should seek the advice of their doctor to make sure that they are clear for the trip.

Altitude Sickness and Acute Mountain Sickness are caused by the reduction in oxygen levels at altitudes above 10,000 feet. To help with the effects of altitude sickness you should allow your body time to acclimatize and cope with the lack of oxygen. The best way to do this is by choosing to climb Kilimanjaro using a route that lasts for 6 or more days, or climb Mount Meru before attempting Mount Kilimanjaro to give your body more time at altitude. There is medication that you can take that will help with the symptoms of altitude sickness; however the only cure is to descend from altitude as quickly as possible. You should never underestimate the dangers of Acute Mountain Sickness and must always follow the instructions of your guide.

Unless you have previous experience of trekking, or climbing at altitude; or you have had an opportunity to experience simulated effects of being at high altitude; it is very difficult to know how you are going to react to altitude, or how well you will acclimatize.

Some people may experience symptoms of altitude sickness from as low as 8,000 feet; however more serious effects would not usually arise until around 12,000 feet. The main consideration is not how high you are going, but how quickly you are gaining altitude.

High altitude is defined in the following three categories:

- High Altitude: 5,000 ft – 11,500 ft

- Very High Altitude: 11,500 ft – 18,000ft

- Extreme Altitude 18,000 ft+ (Kilimanjaro summit 19,340 ft)

- The fact is; young, physically fit males are more likely to suffer from acute mountain sickness (AMS) than any other demographic group. This is largely due to their physical ability to ascend quicker than many other individuals.

Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS)

Acute Mountain Sickness or altitude sickness is very common at high altitude. At over 10,000 feet (3,000 m) approximately 75% of people will suffer mild symptoms of altitude sickness.

Altitude sickness is classified as Mild, Moderate and Severe, with High Altitude Pulmonary Oedema and High Altitude Cerebral Oedema being 2 conditions associated with Severe Acute Mountain Sickness.

Mild Acute Mountain Sickness symptoms include:

- Headache

- Nausea & Dizziness

- Loss of appetite

- Fatigue

- Shortness of breath

- Disturbed sleep

- General feeling of malaise

Symptoms do not usually prevent normally activity but tend to be worse at night. The symptoms usually disappear within two to four days, ascent can continue at a moderate rate as long as the symptoms remain mild.

Moderate Acute Mountain Sickness symptoms include:

- Severe headache that is not relieved by medication

- Nausea and vomiting, increasing weakness and fatigue

- Shortness of breath

- Decreased co-ordination

Symptoms usually make normal activity, such as walking, difficult. The best test for moderate acute mountain sickness is to get the person to walk in a straight-line heel to toe. If a person is unable to walk a straight line it is a clear indication that immediate descent is required.

Severe Acute Mountain Sickness symptoms are an increase in the severity of:

- Shortness of breath at rest

- Inability to walk

- Decreasing mental status

- Fluid build-up in the lungs

- Severe Acute Mountain Sickness requires immediate descent to a lower altitude.

High Altitude Pulmonary Oedema (HAPO) symptoms include:

Shortness of breath (at rest)

- Tightness in the chest, and a persistent cough bringing up white, watery, or frothy fluid

- Marked fatigue and weakness

- A feeling of impending suffocation at night

- Confusion and irrational behavior

High Altitude Pulmonary Oedema results from a lack of oxygen resulting in a buildup of fluid in the lungs. This fluid prevents effective oxygen exchange and as the condition worsens the level of oxygen in the bloodstream decreases, which leads to cyanosis, impaired cerebral function, and ultimately death. Anyone suffering from symptoms must be evacuated to a medical facility for treatment.

High Altitude Cerebral Oedema (HACO) symptoms include:

- Headache

- Weakness

- Disorientation

- Loss of co-ordination

- Decreasing levels of consciousness

- Loss of memory

- Hallucinations & Psychotic behavior

Coma

High Altitude Cerebral Oedema results from a lack of oxygen resulting in a build up of fluid in brain causing swelling of brain tissue. High Altitude Cerebral Oedema usually occurs after a week or more at high altitude. Severe cases can lead to death if not treated quickly. Anyone suffering from symptoms must be evacuated to a medical facility for treatment.

The main concern when climbing Kilimanjaro is altitude sickness. This condition is an acid-alkali imbalance in the blood and body fluids which affects climbers indiscriminately. Whatever your level of fitness, it may not reduce your chances of getting some degree of altitude sickness because almost everyone does – mild headache, nausea, tiredness, loss of appetite are common symptoms.

For your safety you should definitely not be climbing at altitude against your doctor’s advice. You should not climb at altitude if you have sickle cell disease, recurrent pneumothorax (burst lung), pregnant (above 3,500m), a respiratory problem, sore throat, cold, cough, increased temperature or a nose bleed. People who have had laser surgery for short sight may experience vision changes (over 4,500m).

There are no hard and fast rules about who will be affected by these illnesses. Some Himalayan experts who have been climbing for years can experience altitude sickness; meanwhile, inexperienced climbers going high for the first time might feel fine all the way to the top of Kilimanjaro.

The major illnesses are outlined below, but these are such serious issues you should research these ailments further on your own.

High-Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE)

The most serious altitude-related illness and is caused by a lack of oxygen and is called High-altitude cerebral edema (HACE). The large and small arteries of the brain dilate so they can carry more blood and more oxygen, causing the brain to swell.

One of the obvious results of this swelling, or cerebral edema, is a tremendous headache. Other symptoms are confusion, hallucination, an inability to control emotions, and a staggering walk. The staggering walk is often one of the most definitive ways of identifying a HACE victim. Ask the victim to walk heel to toe along a straight line; if the victim has a problem with that they are in trouble and need to descend.

As with HAPE, it is imperative to get the victim to a lower elevation as quickly as possible. Carry the person if you must! Don’t wait for helicopters. The victim must descend until fully well and with absolutely no residual loss of coordination (ataxia).

High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE)

An accumulation of fluid in the lungs, can come on quickly and kill a victim within a few hours. Symptoms of High-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE), include: exhaustion, difficulty in breathing (at rest), chest pain, a gurgling noise in the chest, and a cough with bloody sputum (saliva mixed with mucus).

The best treatment (the only treatment) is to get the victim to a lower elevation as soon as possible, even if that means carrying the person. Oxygen is often used to treat HAPE on mountaineering expeditions (in conjunction with a hyperbaric bag if available), but the best treatment is a fast and immediate descent. The victim should be kept warm or the pressure in their pulmonary vessels may increase even further, and you don’t want that. Adalat (nifedipine) is an important treatment and is used to decrease the pulmonary pressure by dilating the pulmonary blood vessels.

Altitude sickness medicine (Diamox)

Acetazolamide (diamox) is used for the treatment and prevention of altitude sickness; diamox does not mask the symptoms altitude sickness but actually helps to treat the problem. Side effects of taking diamox include; tingling of fingers, toes and face. Carbonated drinks tasting flat. Increased urination and occasionally blurred vision. It would be advisable to take a trial course prior to going to Kilimanjaro as any severe allergic reactions are easier to treat here than at a remote location.

Nutritional Altitude Supplement (ALTI-VIT)

ALTI-VIT is a unique vitamin formula which has been developed to support your bodies requirements at Altitude. Its ingredients include: Siberian Ginseng, Vitamin C, Reishi Mushroom Extract and Ginkgo Biloba, ALTI-VIT is a nutritional altitude supplement to assist with: oxygen uptake, energy production, immune function and sleep quality. ALTI-VIT contains 100% natural ingredients and is available without prescription. More information on the benefits and effects can be found on the ALTI-VIT website.

Analgesics (pain killers)

Ibuprofen/Nurofen is effective at relieving altitude induced headaches.

Acclimatization

- Most of the steps to aid your acclimatization and reduce the symptoms of altitude sickness will be taken by your guides, but it may be useful for you to know some preventative measures along with a few of the signs and symptoms.

- On arrival in Moshi, do not overexert yourself, or move higher for the first 24 hours after arriving. We recommend that you take it easy, perhaps by relaxing by the pool.

- Climb high and sleep low; when possible, sleep at an altitude lower than the highest point you have walked to.

- If you begin to show symptoms of moderate altitude sickness, don’t go higher until symptoms decrease.

- If symptoms increase, go down! Always take the advice of your guide as your health and safety is the most important thing to them.

- Remember that all people acclimatize at different rates. Do not worry if you appear to be the only person in your group suffering, it may just be that it has affected you sooner than other members of your group.

- Stay properly hydrated; acclimatization is often accompanied by fluid loss, so you need to drink lots of fluids to remain properly hydrated (at least four to six liters per day). Urine output should be copious and clear to pale yellow.

- Take it easy and don’t overexert yourself. I cannot emphasize strongly enough the words of the guides “pole, pole” meaning slowly, slowly. It really will increase your chances of getting to summit.

- Avoid tobacco, alcohol and other depressant drugs including, barbiturates, tranquilizers, sleeping pills and opiates such as dihydrocodeine. These cause a worsening of symptoms.

- Eat a high calorie diet while at altitude.

Hypothermia and Frostbite

East Africa’s mountains lack the extremely cold temperatures found in many mountain ranges of the world, but hypothermia and frostbite can still occur.

Hypothermia is a condition in which the body’s core temperature drops below normal. The victim becomes weak and often begins to shake. The obvious response is to warm the victim by providing warm liquids, high-energy foods, hot-water bottles, and even crawling into a sleeping bag with the person (both of you nude for better heat transfer).

In frostbite, soft tissue is destroyed as body fluids freeze into crystals around the cells of the tissue. In the initial stages, the skin is white and hard.

In mild frostbite, when the skin is still soft (sometimes called “frostnip”), the affected area can be rewarmed fairly easily by placing the part someplace warm—under an arm, in a sleeping bag, in the crotch, or against the bare skin of a companion (the chest is good). The rewarming process may be painful, but is usually without long-term problems.

When an appendage is seriously affected by frostbite, the best thing to do is to evacuate the victim without rewarming the frostbitten area. Rewarming a frostbitten area often causes more damage than the actual frostbite. Often, a victim can walk out on frostbitten feet but must be carried if the feet are rewarmed.

If your evacuation must include another night out, rewarming the frostbitten area is inevitable. Modern medical thinking now dictates that rewarming be done quickly. Use water between 38 and 41 degrees Celsius (100–105 degrees Fahrenheit) and soak the frostbitten part for 30 minutes. Do not massage the affected flesh in any way. Once the frostbitten area is warm, wrap it with a loose bandage and keep it warm until a full evacuation can be made. Refreezing of a frostbitten part will cause further damage.

The best prevention for both hypothermia and frostbite is to dress properly. Dress in wools and fleece fabrics; never wear cotton clothing! You should also keep yourself well hydrated and well fed.

Denial

Denial is a huge issue on big mountains, especially with people who are adamant about reaching the summit. You need to admit when there is a problem. Don’t succumb to denial just because you are weak or because you aren’t leading the pack. Denial can lead to the very serious, life-threatening problems described above.